According to Chinese Mythology, Ling Lun (2697 BC) was the legendary founder of music. During the time of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi), Ling Lun constructed bamboo pipes so carefully tuned to the sound of the birds. The Yellow Emperor, reigning from (2697-2596 BC), is said to have ordered the casting of bells in tune with these flutes. From this early development, the Chinese 5-tone musical scale was established (In Western Solfeggio the notes were equivalent to Do, Re, Mi, So, and La, and were called Gong, Shang, Jiao, Zhi and Yu.

According to Chinese Mythology, Ling Lun enchantingly captured the sound of the phoenix; or Fenghuang; a bird that reigns over all other birds in East Asia. There have been images of the phoenix dating back some 8000 years ago during the Neolithic Hongshan Culture in Northeastern China (4700-2900 BC). Together, the mythological Phoenix and Dragon are a balanced couple, further representing the Taoist idealism of Yin and Yang. In ancient times, The Feng was deemed as male, while the Huang denotes a rather feminized beauty, delicacy, and peacefulness. suggesting “how opposite or contrary forces are interconnected and interdependent in the natural world; and, how they give rise to each other as they interrelate to one another” (Wikipedia-Yin and Yang). Today, these symbols are entirely reflected and translated throughout Imperial culture in China. When portrayed with the dragon as a symbol of the Emperor, the phoenix becomes entirely feminine as the Empress, and together they represent both aspects of imperial power.

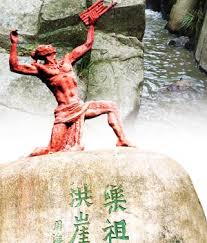

Another piece of mythical Chinese Philosophy credits Kui as the inventor of music. Not to be confused with another mythical Kui- the one-legged mountain demon, this Kui was said to be the heroic creator of music and dance. Kui “[made] a drum by stretching an animal skin over an earthen jar that defeat[ed] another monster”. (Wikipedia- Ling Lun). In relation, Emperor Shun (2317-2208 BC) was a legendary leader of China, and is greatly honored throughout Chinese history. Great Shun, as they called him, had appointed Kui as his musical master and director.

As quoted in the Canon of Shun,

“Teach our sons, so that the straightforward shall yet be mild; the gentle, dignified: the strong, not tyrannical: and the impetuous, not arrogant. Poetry is the expression of earnest thought; singing is the prolonged utterance of that expression; the notes accompany that utterance, and they are harmonized themselves by the standard tubes. (In this way) the eight different kinds of musical instruments can be adjusted so that one shall not take from or interfere with another; and spirits and men are brought into harmony.’ Kui said, ‘I smite the (sounding-) stone, I gently strike it, and the various animals lead on one another to dance.”

[…] When the sounding-stone is tapped or struck with force, and the lutes are strongly swept or gently touched, to accompany the singing, […] (In the court) below (the hall) there are the flutes and hand-drums, which join in at the sound of the rattle, and cease at that of the stopper, when the organ and bells take their place. (This makes) birds and beasts fall moving. When the nine parts of the service, as arranged by the Di (Earth), have all been performed, the male and female phœnix come with their measured gambolings (into the court).’ Kui said, ‘Oh! when I smite the (sounding-) stone, or gently strike it, the various animals lead on one another to dance, and all the chiefs of the official departments become truly harmonious.”- (Chinese Text Project- Canon of Shun).

Emperor Shun is later accredited with originating the music called Dashao; a symphony of 9 musical instruments covering both chamber and lyrical music.

Today, there is a shrine called Jiuyi Shun to both honor and respect the Great Shun. It is rumored that Emperor Shun was buried in the Jiuyi mountain range near the Southern Hunan Province of China.

When Zhang Qian (a Chinese official from the Han Dynasty) visited various countries in the Western regions through the years (138-115 BC), the result was ultimately a great deal of cultural exchange of both culture and foreign instrumental knowledge. The changes that were most seen were with the flute, which up until this point was played vertically. Now that they could be played horizontally, the “flute” became the instruments official title, while aerophonic instruments that were played vertically were called the “xiao.” (See video below) Both instruments are equally important to Chinese culture. Through vicious war and affliction, “the Han Dynasty (206 BC- 220 AD) faced the same threat that plagued every indigenous Chinese government throughout history – the danger of raids by the nomadic peoples of the steppes. To the north and west, China borders on desert and range-lands that have been controlled by various nomadic peoples over time, including the Uighurs, Kazakhs, Mongols, Jurchens (Manchu), and the Xiongnu” (Szczepanski 1). This collapse resulted in a China that was divided into 3 kingdom regions: Wei in the north, Shu in the southwest, and Wu in the center and east. It was a period so famously regarded as The Three Kingdoms (220- 280 AD). This partitioning of powers led to a fragilely segmented country for the next 400 years. With regards to the series of wars, there was a great deal of cultural exchange which in turn paved the way for a great deal of instrumental variation. Gradually, the instruments introduced to China through the Silk Road marketplace became important to the musical life of the country. In general, the Silk Road was “central to cultural interaction through regions of the Asian continent connecting the West and East by linking traders, merchants, pilgrims, monks, soldiers, nomads and urban dwellers from China to the Mediterranean Sea during various periods of time” (Wikipedia- Silk Road). “The Xiongnu (an ancient nomadic-based people in Northern China/Mongolia) adopted Chinese agricultural techniques, dress style, and lifestyle. On the other hand, the Chinese adopted Xiongnu military techniques, some dress style, and music and dance” (Wikipedia- Xiongnu). The following map indicates the Xiongnu territories in (250 BC).

Xiao, Xun and Guzheng (Chinese zither) Trio:

Overtime, the Chinese made their modifications to the foreign introduced instruments that had become readily available. An example of these changes is transparent with the Chinese Ruan Xian. Formerly, the instrument was called the Qin Pipa (Qin Dynasty 221 BC- 206 BC). It wasn’t until the Tang Dynasty (8th Century) that the name Ruan was given.

Prior to this change, the instrument was made of copper and had a round sound box, and 13 frets on its neck. Revisions made way for the modern Ruan; with 24 frets and 12 semitones on each string. Also, the strings were previously made of silk, while today’s Ruan has steel strings.

The following picture (found in an Eastern Jin or the Southern dynasties tomb) depicts Ruan Xian playing the instrument so formally named after him. Ruan Xian was a musician and scholar during the Three Kingdoms. It was said that he and six other scholars (The 7 Scholars) would get enjoyment from drinking, writing poems, playing music, and simply enjoying life away from the corruption of the government.

One of the most well-known Chinese instruments, called the Pipa, has a pear-shaped sound box and crank-handled strings. This chordophone was indefinitely prominent throughout early Chinese musical culture. Similar to the way a western guitar is played, the Pipa was at first played horizontally as the musician plucked the strings with a plectrum. Today, the Pipa is played much differently; It is gently placed on its players lap, rested against the shoulder, and played vertically. According to Qiao Jianzhong, former director at the Music Institute of China Art Academy, “it took more than a thousand years before it was being played vertically as it is on the stage today. That period lasted from the 7th century in the Tang Dynasty to the 17th century in the Ming Dynasty” (Chinese Civilization- History of Chinese Instruments). The Chinese introduced the Pipa to Japan, and even today, the Japanese play it horizontally, with a plectrum.

As quoted by Po Chu-Yi (also known as Bai Juyi (772-846 AD). in his “Song of the Pipa Player”:

“She brushed the strings, twisted them slow, swept them, plucked them — […] The large strings hummed like rain, The small strings whispered like a secret, hummed, whispered-and then were intermingled, like a pouring of large and small pearls into a plate of jade.”

The Tang Dynasty brought about a rich array of musical instruments, many of which are neither played or constructed today. Now extinct, the Konghou, an Chinese ancient harp, was introduced to China through China’s western regions. The Paiban, a clapper made from several pieces of flatwood or bamboo, produces a sharp clapping sound. It was introduced to the Tang Dynasty through today’s northwestern regions. “According to historical records, there were about 300 kinds of musical instruments during the Tang Dynasty- and some of them can still be found in Japan today” (Chinese Civilization- History of Chinese Instruments). In many ways, many of the musical traditions from the dynasties are still represented in Chinese culture today. In Xi’an, one of the oldest cities in the People’s Republic of China, a group of musicians still play imperial music from the Ming dynasty- using up to 7 types of drums. The score of their ensembles depends on the beat of the drum throughout the song. The drum is extremely important throughout this culture, as it ties the instruments in the ensemble together as a unit while playing.

Traditional Chinese Opera roots back to the 3rd century CE. Jingiu represents capital city operas, such as Beijing or Peking. “Chinese opera is seldom publicly staged in the 21st century, except in formal Chinese opera houses, and during the lunar seventh month Chinese Ghost Festival in Asia as a form of entertainment to the spirits and audience. These masks were based on the ancient face painting tradition where warriors decorated themselves to scare the enemy” (Wikipedia- Chinese Opera). String instruments (like the Jinghu or Erhu fiddle), percussion, and various wind instruments are a requirement to accompany Chinese Opera. “For many years men had to play women’s roles, singing in falsetto (head voice), because women were often banned from the stage as the theater was seen as morally corrupting. Today, women are not only playing their own roles, but often men’s roles as well, while some men continue to impersonate women” (Miller and Shahriari 206). The traditional roles are broken into sections: Sheng (male roles) which can be subdivided into young, old and military men, Dan (female roles) similarly subdivided, Jing (painted face roles) featuring facial patterns that symbolize the person’s character, and Chou (comedians) that are easily identified by the white patch in the middle of their faces.

This Chinese Opera is about a maiden who died and was revived for love. It was composed around 1600 AD by poet, Tang, Xianzu (1550-1616).

One of the most important instruments to Chinese culture is the Erhu, though it did no originate in China! Though it did become readily apparent in China over a thousand years ago. The Erhu sounds a lot like the human voice, as it has the ability to express deep and sorrowful emotions. The bowed, 2-stringed Chinese spike-fiddle may have originated within the nomadic cultures, within the Xi tribe; as the instrument was once called the Xiqin, introduced to China through the Silk Road in the 10th century. It’s musical timbre is mid-ranged, with an extremely wide and expressive range. The Erhu is used to accompany Operas, song and dance, as well as being implemented as both a solo and small ensemble instrument. “Perhaps there is no instrument more evocative of China..” (Youtube- Danwei- The Erhu). However, there was no record of the Xiqin/Erhu until the Song Dynasty; demonstrating that it was a product of the integration of Chinese and foreign cultures.

Ancient Chinese regard music as both holy and pure, and believe that it has the power to purify people’s thinking. The harmonious combination of sounds was made by instruments that fell into 8 categories called Bayin; instruments made from metal, stone, clay, wood, bamboo, string, gourd, and leather. The particular sounds and timbres produced by these instruments revealed one’s soul to the listener.

As an ancient 12-tone musical system, the Chinese chromatic scale, or Shí-èr-lǜ, uses the same intervals as the Pythagorean Scale. This particular tuning scale is considered the untempered, or a pure perfect fifth, using a ratio of 3:2. Essentially, this one of the most stable or consonant scales, as well as being easy to tune by ear.

By the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) periods in China, cultural instruments had fully ripened- taking shape as relevant entities throughout Chinese tradition and culture. Bowed string chordophones were represented by the Erhu, Jinghu (higher pitch; used in Beijing Opera) and Gaohu (used in Cantonese Opera) (had minor shape, and tonal differences), the plucked string chordophones, represented by the Qin (a fretless ancient zither) and Pipa, wind instruments that were represented by the flute, Xiao (vertical bamboo flute), Sheng (consisting of 21 reed pipes and a metal base), and Suona (a double-reeded horn with a squeaky, loud, buzzy timbre- often played outdoors in northern folk ensembles), and finally percussion instruments that were represented by the Tanggu (ceremonial hall drum played with 2 sticks), and Bo (small idiophonic cymbals that are clashed together and have a high pitch and brassy timbre).

There was a time when the Qin/Guqin was the connoisseurs’ choice of music within the high court. Many of the played pieces seem to have no detectable tuning because “tablature” (notation consisting of charts that indicated how to pluck, or touch each string), did not include instructions on tuning. Therefor, each instrument truly had its own character, and was a rather acquired taste. The Qin/Guqin is rarely played today, but the instruments are often collected as ancient art pieces in their own regard. The instrument is fundamentally pentatonic, as its “plucked sounds [are] produced [by] the nail or flesh of the finger, [and] tone bending [is] creat[ed] by the sliding movements of the left hand. The use of harmonics (clear, hollow sounds [are] produced by gently touching the string at the node), [and] scraping sounds are produced when the player slides the left hand along the rough textured strings. […] The notation for the Qin is in a form called “tablature” consisting of a chart the indicates how stop to pluck, or touch each string” (Miller and Shahriari 194). The instrument was quite often passed down for generations within the same family, so many of them are still around today.

The Chinese Sheng (pictured below) looks vaguely similar to the wooden pipes of the Hulusheng (gourd mouth organ)…which is again similar to the Cambodian M’baut. Read my post on the M’baut here! 🙂

The Hulusheng dance of the Yi Minority

Here’s a video of an ensemble featuring a Suona:

One of my favorite ancient instruments that I discovered is within the stone category. The Bianqing, or individual “sounding stones” qing, were flat L-shaped stones, and when many of them were hung together on a frame, they became “Bianqing.” At the time, someone would strike the stones with a mallet in order to produce various melodic tones. The Bianqing, as well as the Bianzhong (a set of bronze bells- dating back to 433 BC) were important in China’s ritualistic music of the courts.

The Chinese aerophonic ocarina, or Xun, was made of baked clay or bone. It’s globular Earth-like shape has stayed the same for 7 thousand years, making it one of the oldest musical instruments in the world.

In fact, the oldest musical instrument was found in China; a 7-9000 year old Neolithic bone flute, made from the wing-bones of the crane. “The discovery of these flutes presents a remarkable and rare opportunity for anthropologists, musicians and the general public to hear musical sounds as they were produced nine millennia ago” (Harbottle 1).

Sources:

“Chinese Instruments.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 23 Feb. 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_instruments>.

“Emperor Shun.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 16 Feb. 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Shun>.

“Emperor Shun.” Emperor Shun. Silkquin.com, n.d. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://www.silkqin.com/09hist/qinshi/shun.htm>.

“Erhu.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 24 Feb. 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erhu>.

“Fenghuang.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 19 Feb. 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fenghuang>.

Harbottle, Garman. “Oldest Musical Instruments Dated.” Oldest Musical Instruments Dated. Bookhaven National Laboratory, 22 Aug. 1999. Web. 27 Feb. 2014. <http://www.bnl.gov/bnlweb/pubaf/pr/1999/bnlpr092299.html>.

“Hongshan Culture.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 02 Apr. 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hongshan_culture>.

Hongda, Fan, Dr. “China’s Policy Options Towards Iran.” Mideast.shisu.edu. Department of Political Science, School of Public Affairs, Xiamen University, n.d. Web. 26 Feb. 2014. <http://mideast.shisu.edu.cn/picture/article/33/50/46/9f510620432f8f643e78b9058401/8502b7bf-b1cf-49a0-bef7-47cac0814415.pdf>.

“Konghou.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Dec. 2013. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Konghou>.

“Kui (Chinese Mythology).” Absolute Astronomy. AbsoluteAstronomy.com, n.d. Web. 25 Feb. 2014.<http://www.absoluteastronomy.com/topics/Kui_(Chinese_mythology)>.

“Kui (Chinese Mythology).” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 24 Feb. 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kui_%28Chinese_mythology%29>.

“Qing Dynasty.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 25 Feb. 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qing_Dynasty>.

“Ruan.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 13 Jan. 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruan>.

“Silk Road.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silk_Road#cite_note-2>.

Szczepanski, Kallie. “Why Did Han China Collapse?” About.com Asian History. About.com, n.d. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://asianhistory.about.com/od/ancientchina/f/Why-Did-Han-China-Collapse.htm>.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Xiao (musical Instrument).” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2014. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/273813/xiao>.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Qin (musical Instrument).” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2014. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/111666/qin>.

“Three Kingdoms.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 22 Feb. 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Kingdoms>.

“What Is the Significance of the Dragon and Phoenix in Chinese mythology?” Yahoo! Answers. Yahoo!, n.d. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20071114110649AA2QKYj>.

“Xiongnu.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 24 Feb. 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xiongnu>.

“Xun (instrument).” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 16 Feb. 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xun_%28instrument%29>.

“Yin and Yang.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 23 Feb. 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yin_and_yang>.

Yu, Han. “English Translation of 300 Selected Poems from Tang Dynasty.” English Translation of 300 Selected Poems from Tang Dynasty. Chinapage.com, n.d. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://www.chinapage.com/poem/300poem/t300b.html>.

”

”